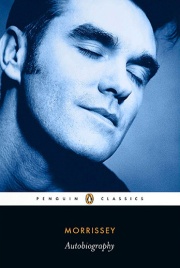

NO MATTER WHERE YOU RUN, YOU JUST END UP RUNNING INTO YOURSELF. AUDITING THOSE DAYS WHEN IT WAS ALL TOO MUCH, OR NOT ENOUGH, OR ALL POINTS NOWHERE AND SOMEWHERE BETWEEN, THE PUBLICATION OF AUTOBIOGRAPHY PROFFERS A QUITE REMARKABLE ACCOUNT OF MORRISSEY’S TROUBLED PASSAGE THROUGH LIFE THUS FAR…

When the cultural attention span tends to butterfly glibly somewhere in the vicinity of reductive caricatures and the currency of self must most frequently be paid over in 140 characters or less – or else – the sprawl of 457 unchaptered pages from He Who Is Professionally Miserable might be an antiquated and somewhat unattractive proposition. Yet more may sometimes be more and, on this particular occasion, more is.

When the cultural attention span tends to butterfly glibly somewhere in the vicinity of reductive caricatures and the currency of self must most frequently be paid over in 140 characters or less – or else – the sprawl of 457 unchaptered pages from He Who Is Professionally Miserable might be an antiquated and somewhat unattractive proposition. Yet more may sometimes be more and, on this particular occasion, more is.

Thrown straight out onto “streets to define you and streets to confine you” in monochromatic ’60s Manchester (a childhood cage where “sadness is habit-forming” and all potential horizons seem to be obscured) to a wintry post-show street in Chicago where “a small boy of 52” clings to his life-raft conviction that music ought to mean something (singing songs that did once, do still and will yet come to), Morrissey’s AUTOBIOGRAPHY is a rollicking tour-de-force which explodes all emotions within. Often simultaneously.

The predictable howls will rise as, in the current moment, it seems to have once again become the agenda to look only from one angle and jab at the chin – alongside the handily cooling caveat of having only ever appreciated Morrissey’s talents when in The Smiths. The audacious, frankly silly, joke that this book finally reaches publication as an immediate Penguin Classic has fallen on austere and deaf eyes, stretching already worn patience. Yet, even after levying all of the pretensions, fashions, faults and falls from grace which black-dog its author, the plain truth remains that AUTOBIOGRAPHY is affecting in-and-of itself in a way which few rock tomes have been. Dylan’s imperial CHRONICLES: VOLUME ONE nestles head-to-toe, surprisingly, as its closest well-written bedfellow.

Any note of Morrissey’s facility for language – even an awareness gained from familiarity with his lyrics – offers little genuine protection from the surprising rush as AUTOBIOGRAPHY’s prose busts loose. Morrissey involves quickly, a rat-a-tat salvo invigorating the drabness of a down-drag childhood spent kicking along humdrum streets – which were razed shortly after he’d passed through. As is authentically the way memory compresses experience down to a squint, yet the distant is unpacked and glared at without the trick of overly fanciful embellishment, still revealing all detail that ought to be known.

A brief accidental encounter with the cast of CORONATION STREET enlivens only a few lines just as, within a paragraph, the compound tragedy of his aunt Jeane’s slum life is mourned. The cruelty of the Catholic church and the cycle of domestic violence (returning to a husband who, of nothing, had punched her in the face on the street) takes a noose to the heart, word by word. Jeane and the brazen and untameable Johnny tried and they failed – yet somehow they just continued to continue on. They come and they go, but they never leave young Steven, mute kid witness to grim public assault, and not sure what happiness means. And so it begins, having already begun.

Morrissey clambers up during the search of teenage years, out through the salvation of pop music, and on to profound creative marriage to Marr and the alchemic new family he names The Smiths. Then there becomes a beyond. Giddy, dizzy, London becomes Camden neighbour Alan Bennett, his garden backing on to Morrissey’s, delivering relationship mediation; out of her shoes and in your face Sandie Shaw ignored at the door but climbing in through the window anyway; and warm and lovely Kirsty MacColl turning up with a corner-shop carrier bag full of cheap tinned ales. The Smiths rise to renown with little record company might propping them, but four years of it drains songwriting partners and breaks bonds. Morrissey – sad and “as if behind glass” – wonders why no-one around the band suggests that they just disappear somewhere to rest, and breathe apart.

Solo debut VIVA HATE, made in 1988, means Morrissey mops up The Smiths’ contractual obligations singlehanded, whetting the appetite for pressing on as is. Years pass with artistic highpoints (career-best VAUXHALL AND I) and expiring record contracts and fired managers and the USA and the NME and a fall and a resurrection, and stalking death – including that of friend / producer Mick Ronson. And two (presumably sexual) relationships; one with a man (“the I becomes we”) and one a woman (with whom the possibility of having a child is raised). The unanswered question appears to be answered on these pages – though Morrissey has since reclaimed himself from your mere conventional categorisation. He is, apparently, humasexual. So, yes, what you probably thought. But, no, probably not what you thought.

Only once does AUTOBIOGRAPHY seem close to crashing – the author hemming himself in, a bore between archnesses, during an aggressive, arid, pained and dispiriting 50-page deconstruction of that court case. It leaves froth on the lip and all weights dragging. However, regardless of each moral perspective on The Smiths’ internal financial arrangements, if Morrissey’s account of the legal proceedings is to be believed then injustice did seem to be served and ranks then twisted and closed around it. So it should be no surprise that he labours the point by dedicating almost as much of his AUTOBIOGRAPHY to the wrongfulness of The Smiths’ protracted, utterly squalid, denouement as he does to the band’s bright and brief flame.

As the gavel slams down he sits in the courtroom with those other parties, wondering how these ugly events have come to define their lives more than the beautiful THE QUEEN IS DEAD ever did, and it’s a sobering, deeply embittering, moment. But, even then, the surprise of hope arrives – not for the resurrection of the band (who in their right mind, or their left mind, would clamour to see that vulgar picture anyway?) but for the rescue of Morrissey from his insistence that he is an island.

“The passing of time,” he says, reflecting on a tellingly conciliatory letter sent to him several years later by Mike Joyce (or Joyce Iscariot as he often calls him), “might mellow you into forgiveness. It doesn’t mean that you ever again want to be friends”.

As often as he charges depths in despair, Morrissey breaks surface in humour (David Bowie as an awkward straight-man stooge; quiffed band-member Alain Whyte applying hair-gel to go to bed in), and much is self-deprecating (falling into Glastonbury mud as he comes offstage; slipping, fully clothed, into a hotel swimming pool). There is also gentle kindness (tending to a run-over cat; nurturing an injured fledgling – a scene peculiarly reminiscent of Tony Soprano’s neurotic obsession with the ducks in his pool).

But it can sometimes be hard work reconciling the tenderness or selfless behaviour with the petty cruelty, nastiness and score-settling served out to people he dislikes or, occasionally, to those he probably does. Not amongst that select latter number are writer Julie Burchill, singer Siouxsie Sioux and Rough Trade’s Geoff Travis; each, if these tellings be true, earning their scorn and truly getting some – even though the sustained some can be quite hilarious.

Morrissey’s salty wit spices the bread, a distinctive eyebrow arching deadpan above many of the lines here, but a complex lifetime of self-loathing and loving others – and, of course, of loathing others and self-loving – can’t really be leavened quite so casually. A constant push-pull of self-doubt and surety, vicious intolerance and good heart, and wisdom and lack of self-awareness, mark out the Moz presented in these pages as fairly three-dimensional and human after all. The paradox of existence will doubtlessly crash around him ’til the soil falls over his head – just as it collides with these pages, from first to last. “It’s just not that simple”, AUTOBIOGRAPHY seems to radiate in answer to all questions and all caricatures. That is as it should be. He buries many others in this sad, uncomfortable and deeply funny book though by doing so Morrissey does not really spare himself either. Before looking the other way that is, perhaps, only as it should be.

Published by Penguin Classics

Paperback / 480 pages / 129 x 198mm

ISBN: 9780141394817

E-book ISBN: 9780141978444

You must be logged in to post a comment.